Math Anxiety in Undergraduate Students

Increased awareness of mental health is one positive thing to have come from the global pandemic. Maintaining positive mental health is important for everyone. We as instructors need to engage with self care and we need to be aware that our students may struggle and offer supports.

One area where we can support our students is with math anxiety. Math anxiety is real and it can affect not only our students’ career choices, but also their learning. In this month’s blog, we go into depth on one recent article on students’ math anxiety and explore another article that provides ideas for supporting our students with math anxiety.

What is math anxiety and why should we care?

Anxiety about math can occur in students at almost any age. It has been identified in students as young as elementary age and can manifest in high school or college students. It is estimated by researchers that math anxiety affects between 10% and 20% of college students. Math anxiety comes about when students become overly concerned about performance in math and start to believe that their performance is tied to innate talent rather than a skill that can be developed.

We can measure students’ math anxiety with the commonly used Abbreviated Math Anxiety Scale (AMAS), a nine item self-report questionnaire. The items are rated on a 0-4 scale with 0 = no anxiety and 4 = high anxiety and can be split into two subgroups pertaining to learning anxiety, like “listening to a lecture in math class” and evaluation anxiety with items like “taking an examination in a math course.” The AMAS was originally published in 2003 and has since been used to study math anxiety across countries and age groups. The AMAS is a reliable measure of math anxiety for multiple students.

Article Summary

This blog focuses on a 2022 study by Kit W. Cho of the University of Houston-Downtown who uses the AMAS to measure math anxiety in a population of mostly minority college students. The article explores the connection between self-report anxiety levels on the AMAS and performance on mathematics problems. It further validates the AMAS as a good measure for math anxiety in minority undergraduate students.

In this study, over 350 students completed two sets of multi-step math problems - half were difficult with two-digit multiplication and half were easy with a one-digit multiplication step. Students were not allowed any materials, like calculators, for the math problems and the amount of time to answer each problem was recorded. Following the math problems, students were asked to predict what percentage of problems they got correct and then were administered the AMAS questionnaire.

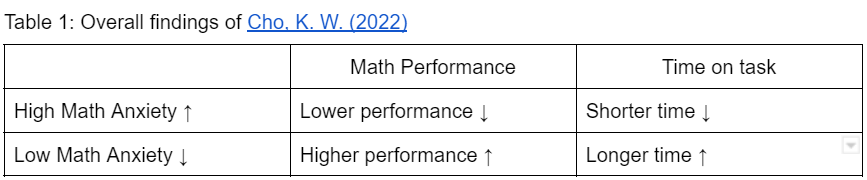

Students predicted their actual performance on both the easy and difficult math problems, indicating that they can self-assess performance accurately. Students with high math anxiety performed lower on the math problems than those with low math anxiety, regardless of if the problems were easy or difficult (Table 1), but they did perform worse on the difficult problems. This finding supports previous studies demonstrating that students with high math anxiety will have lower performance in math.

One key finding of this study is that students who have high anxiety actually spent less time on difficult math problems than on easy problems. This indicates that students with high math anxiety see challenging math problems as something they cannot achieve, so they give up sooner. This finding supports the idea that students with high anxiety may approach math with a fixed mindset rather than a growth mindset. And students’ mindset is something that we as instructors may be able to influence.

Preparing the math classroom environment

We often find students with math anxiety in developmental college math courses. These are students who believe math is an innate talent ( “I’m not a math person”) and who have struggled with past math classes. We can use the Control-Value Theory as a framework to think about math anxiety with these students (Klee, Buehl, & Miller (2022). At its essence, this theory says that the less perceived control students have over outcomes (i.e. they can’t do well at math), and the more they value the outcome (i.e. math is important and I need to pass), the more anxiety they will have..

The math classroom environment can affect how students perceive control and value, and as instructors we can influence the environment in three key ways: instruction, autonomy support, and classroom expectations. Instruction tasks should be appropriately challenging with clear guidelines to give students a sense of control related to those tasks. When students have more autonomy during instruction coupled with appropriate support, they can experience success with tasks. Finally, we as educators must set a classroom expectation that values mastery of learning rather than performance (as on tests).

When students are in a classroom environment that values mastery (success) over performance (not failing) they will have reduced anxiety. This seems like a subtle difference, but it does set students’ mindsets and can affect students' learning success. If students are worried about failure, they use their mental capacity worrying about performance rather than mastery of content - on a negative rather than a positive. So, how can we help students focus on mastery rather than performance and thereby reduce anxiety?

Implications for the Math Classroom

Recognizing that a student has math anxiety is the first step to dealing with it. Administering the nine-item AMAS is one way to make students aware of their own math anxiety. Further, explaining that math anxiety is common, especially with non-math majors and developmental math students, can help students recognize that they are not alone. You may then be able to promote methods to reduce anxiety like writing or mindfulness strategies. Addressing math anxiety directly rather than glossing over the problem can help students recognize and then deal with their anxiety, which can help to reduce it.

Teaching concepts promotes mastery (learning success) while teaching procedures promotes performance (not failing). This means that concept teaching can reduce anxiety and can increase students’ mathematics learning. Problem-based teaching and learning is an ideal way to develop understanding of concepts. Further, this strategy often uses math problems that are embedded in real-world contexts which can engage students, allow them to make meaningful connections and may even address students’ interests.

Problem-based teaching and learning often uses partner or group work to engage with tasks. Allowing students to work with others can reduce anxiety because they can see other students’ successes and failures. Another way to promote group work is to engage students with problem solving first. As shown in this previous blog, problem solving before providing direct instruction has also been shown to increase students’ learning of math.

The way we frame assessment affects students’ math anxiety. It is of note that one the more anxiety-producing situations as identified in the Cho article, is “being given a ‘pop’ quiz in math class.” We want our students to be able to perform math skills quickly, but using a ‘pop’ quiz can increase students’ anxiety which can decrease students’ performance. In other words, a ‘pop’ quiz may not be a true measure of a student’s math ability if they have math anxiety.

Instead, use more frequent, low-stakes, formative assessments with regular feedback. Klee, Buehl, & Miller (2022) suggests having “no penalty” online quizzes where students can reflect on the previous class and/or explain concepts in their own words. Feedback on these quizzes are process-oriented and promote mastery of learning rather than whether a response is ‘correct’ or not. Frequent assessments and feedback can not only increase exposure to potentially anxiety-producing situations, it can also promote the value that learning is more important than performance, thus reducing anxiety.

Summative assessments are an ideal way to check for students’ understanding of math concepts but they can also be high anxiety situations. Talking about anxiety openly before summative assessments can bring awareness to concerns and alleviate fears. Frame assessments as a way for students to show what they know rather than a way to check for what they don’t know. This minor change in view can make assessments a positive rather than a negative, anxiety-producing situation.

Consider allowing supports for students when they take summative assessments. For example, a formula sheet or a small note card can mimic real world situations where students would have these resources available. You may also allow revisions, marking incorrect items, without further feedback, and allowing students to try those problems again. This would take additional time for grading, but it does emphasize the importance of learning, and learning from mistakes, over performance.

Our students may have math anxiety, which prevents them from effectively demonstrating their math understanding. As instructors, we can identify and reduce our students’ math anxiety by focusing on mastery of learning and preparing our classroom environment.

Take aways:

Math anxiety plagues students who stress performance over learning, resulting in lower performance and less time on difficult tasks.

As instructors, we should address math anxiety directly with students, reducing the stigma. We can also frame math as a positive (mastery of learning) rather than a negative (don’t fail).

Problem-based teaching, group work, frequent formative assessments, and support with summative assessments can reduce students’ math anxiety and help them to demonstrate their true math skill.