A relatively recent concept in the field of learning psychology is the Forward Testing Effect (FTE). When students are tested on previously learned information, they are better able to acquire new information. Stated another way, testing improves future learning. The forward testing effect has been described in multiple studies and has implications for how we may use tests and quizzes in the classroom.

The Forward Testing Effect

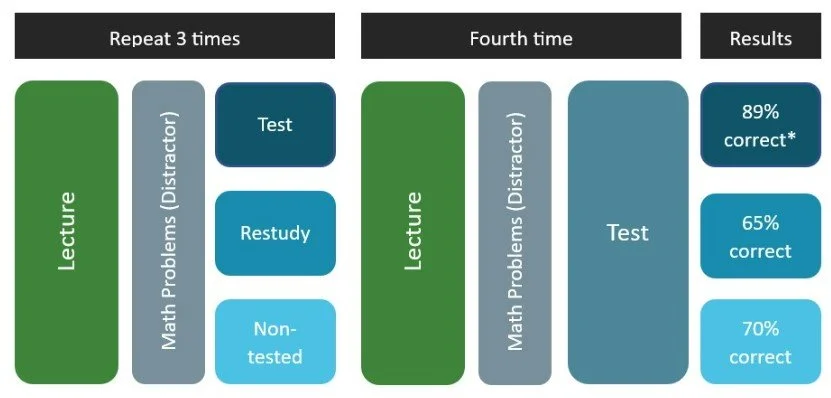

The first description of FTE is found in an article by Szpunar et al. (2013). Undergraduate students were provided with video lectures on statistics and then given math problems to solve as an immediate distractor from what was just learned. Groups of students were then given more math problems (non-tested), asked to review the lecture (restudy) or given an interim test on material from the lecture (tested). This process was repeated three times with three different lectures. In the fourth and final iteration, all three groups were given a test on the material from the last lecture. Students in the tested group scored significantly higher on the final test than the non-tested and restudy groups with a mean of 89% correct test items versus 65% with the restudy group and 70% with the non-tested group (Figure 1). These results indicate that interim testing has a positive effect on future learning – the forward testing effect.

Since the Szpunar article was published, the forward testing effect has been confirmed by multiple studies and with different conditions. The FTE has been demonstrated with memorization tasks like name-face pairs and language learning and with more complex concepts like identifying similarities in artists’ work and content lectures. The FTE has also been demonstrated with various populations like college students, K-12 students, and adults with traumatic brain injuries.

A review article by Yang et al. (2018) covers the literature of FTE to that date and goes further to explain possible mechanisms for why the FTE works. Each mechanism can be grouped into either the encoding or retrieval phase of learning. The mechanisms can also be grouped into whether or not the participants feel motivated to learn as a result of being tested. The mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and most likely there are multiple mechanisms to explain why the FTE exists.

For clarity, we should contrast the FTE with the backward testing effect, which has been well studied and is often simply referred to as the “testing effect.” The backward testing effect says that when information is tested, retention of that information is improved. In other words, the act of testing can improve learning because students are forced to recall what has been learned.

How much testing is needed?

Most studies on the FTE have similar designs. Participants are given a small amount of material to learn, for example 5 minutes of a lecture or 12 face-name pairs. They are then given a distractor like a few math problems to solve to reduce any effect of immediate short-term learning. Then participants are either tested on all learned material or told to restudy (interim test or restudy). After three iterations, all participants are tested on all of the material for the fourth learning session (criterial recall). See Figure 1 for example.

In the classroom, it is not practical to test students on all the information we want them to learn. So, if students were tested on only part of the learned material rather than all of it, would that be enough to see the forward testing effect? This is the question answered in a recent article by Hilary Don et al. (2022) entitled “Do Partial and Distributed Tests Enhance New Learning?”

Given 12 face-name pairs to learn, participant groups were tested on all pairs, told to restudy the full list, or tested on only half of the list (6 pairs). Regardless of how much was tested, participants performed better on the fourth test than the restudy group indicating that the act of testing, even partial testing, increases learning over studying alone.

To further elucidate how much testing is needed, groups of participants were tested or told to restudy 4, 8, or all 12 Euskara-English word pairs during the first three interim testing periods. Again, the forward testing effect was observed in the criterial recall regardless of how many pairs were tested in the interim. The act of testing, even partial testing, contributes to future learning.

Distributed testing is often utilized in the classroom where students are tested not only recently acquired material, but previously acquired information. The Don et al. study demonstrates that testing previous and newly acquired material together is still superior to restudy in that tested participants performed significantly better on criterial tests.

There is a risk in using partial and distributed tests in that testing only a subset of information may impair recall of information that has not been tested. The results of the experiments in the article show that this is not the case. Testing only part of the material to be learned does not inhibit learning of all the information. Stated another way

“There is no reason to assume that partial, or partial and distributed testing is inferior to full testing.” (Don et al., 2022, p.13).

Questions that remain

While the forward testing effect was observed regardless of how much (partial or full) or the type of (distributed) testing was given to participants, there are mixed results on cumulative testing. When participants are given cumulative tests on Euskara-English word pairs from all four learned lists, a total of 48 pairs, there is no significant difference in performance between partial or distributed testing and restudy groups. Cumulative testing involves both forward and backward testing effects, so we cannot attribute results to only one of these phenomena. Some possible reasons for cumulative test results include, but are not limited to, the short time span between learning and cumulative testing, lack of exposure to some word pairs outside of initial learning, or the lack of feedback on interim test performance.

It is known that feedback allows correction of errors and maintenance of correct responses on testing, thus contributing to the backward testing effect. However, the effect of feedback on the forward testing effect is less clear. Most studies on FTE do not involve feedback on interim testing, and those that do have mixed results (see Chan et al. (2018) for a review of this literature). How feedback affects the forward testing effect is another potential area for study.

Another question that remains is the time span between learning and testing. Many studies of the forward testing effect occur in one sitting. It would be of interest to see whether the effect is observed over time akin to what may be seen in a classroom. If participants were given interim tests on single lectures two or three times a week, would the forward testing effect be observed? These practical questions may best be answered by those conducting research in the classroom.

FTE in the classroom

The forward testing effect is a psychological phenomenon that can inform our teaching and learning strategies in the classroom. We know that using low-stakes formative assessments, like quizzes, can help to reduce math anxiety (see previous blog on math anxiety for more information). But the forward testing effect indicates that using low-stakes testing could also promote future learning.

The Don et al. (2022) study shows that we don’t have to test on everything. Rather we can use partial or distributed tests and still see a positive effect on future learning. This makes interim testing of information much more practical for the classroom setting. Whether these tests help to improve encoding of new information, promote a shift in strategies for recall, increase motivation for learning, or a combination of these mechanisms remain to be determined. Regardless, what is known is that interim testing promotes new learning.

“The main take away is to use tests or quizzes that tend to be low stakes, not stressful for students, and use them throughout learning to benefit future learning.” ~ Dr. Hilary Don

Take Aways:

- Administering low-stakes quizzes on previously learned information could lead to increased learning by students in the future, a phenomenon known as the forward testing effect (FTE).

- It is not necessary to test all information to see the FTE. Short quizzes on part of immediately learned or past learned (distributed) information is effective.

- As an added bonus, using low-stakes quizzes may reduce test anxiety and math anxiety.

Thank you to Dr. Hilary Don for providing input on this blog article.

For an explanation of the published study by Dr. Hilary Don, see this video from the Experimental Psychology Society published in January of 2023.

.jpg)