Classroom instruction has changed from the traditional lecture to active and engaging strategies of teaching and learning. Likewise our assessment practices must change from the use of summative tests and quizzes to more robust methods of gathering and using assessment evidence. In this first of what is likely to be many blogs on the topic of assessment, I will provide the big picture view of assessment that I share with my preservice teachers on the first day of their semester-long class on assessment and technology.

“Classroom instruction has changed from the traditional lecture to active and engaging strategies of teaching and learning. Likewise our assessment practices must change.”

There are three reasons I want to share thoughts on assessment with you. First, I really like assessment (nerd-alert!). To learn more about assessment is the reason I went to graduate school a second time. Second, assessment is continually in the news because of its importance for state and federal accountability, teacher evaluations, advancing students, college admissions, and more. Third, as our instruction strategies have changed, so too the landscape of assessment is changing. We have moved away from the No Child Left Behind era with its standardized testing that distills results to simple numbers, towards robust and qualitative practices like portfolios, standards-based grading, and individual classroom assessments. So, without further ado, let’s start this journey...

Assessment as a Science

As teachers of math and science, logic appeals to us. There is a beauty in “If A=B and B=C then A=C.” As long as a science experiment is set up properly, you will get approximately the same result as nature obeys its laws, every time. In the realm of teaching and learning, assessment is the closest thing you can find to logical scientific experimentation.

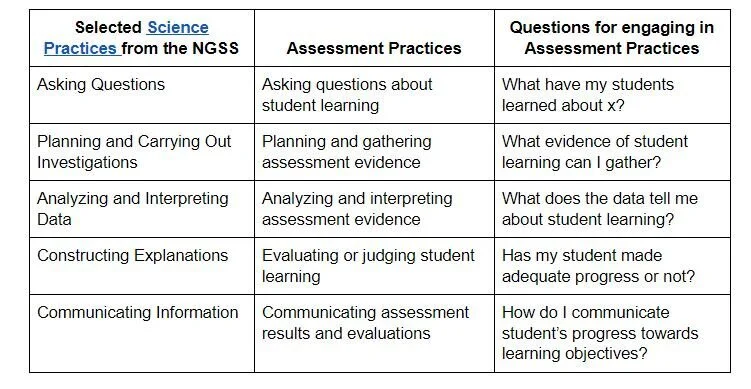

The practices of assessment are akin to the practices of science as defined in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). Science starts with asking questions. For assessment, the questions revolve around the extent to which students have learned. Both involve planning and gathering data. This data needs to be analyzed and interpreted. With assessment, the data is often distilled to a judgment of whether the students have made adequate learning progress or not. Finally, this judgment is communicated to the student, traditionally with report cards.

Selected Science Practices from the NGSS

The scientific practices can stand-alone but most often are used in a more or less linear process from question to investigation to data analysis to explaining. Likewise, assessment can be considered as a process from question to evidence to analysis to judgement. Thinking about assessment as a science will ensure alignment - that the assessment evidence and the way we analyze and judge the evidence can answer the question of what our students have learned.

Assessment as a Road Trip

While assessment and science are logical processes, the assessment practice that can make or break this logic is the “planning and gathering assessment evidence.” In science, to adequately answer the question, it is necessary to have many investigations allowing for multiple and varied data to be analyzed. Likewise, with assessment, there is a need for multiple assessment evidence that demonstrates student learning. When teaching my preservice teachers about this assessment practice I use the analogy of a road trip.

I have family in Hilton Head Island, South Carolina (objective). It is a very nice place on the Atlantic Ocean with palmetto trees and road signs that are small and are buried in foliage for beautification purposes (summative evidence). I live in Illinois in a village that is considered a suburb of Chicago (starting point). There are many different ways for me to get from here to there - through Kentucky or Ohio or other states - and different routes give me different experiences (formative).

When planning a trip, you first need to be specific about your destination. With assessment, you likewise need to be specific about your destination - the learning objective. The clearer you articulate your learning objective, the more focused your assessment journey. How will you know you have reached your destination? You need evidence from a summative assessment that can demonstrate ideal achievement of the learning goal. Articulating the objective and determining the acceptable evidence are the first two parts of Backward Design championed by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe.

In a very traditional view of assessment, this is where things end. You know where you want to end up and you know what it will look like when you get there. You teach, you give students a summative test, and everyone hopes for the best. But in a modern view of assessment, there are two additional pieces to this assessment journey. To get to where you want to go, you have to know where you are starting from. I live outside Chicago, but my trip will be different if my starting point is in Gurnee or in Joliet. But what if I miscalculated and I’m actually in Minneapolis? Then, my plan will be very different! This is why pre-assessment is an important piece of a robust assessment plan. To get your students to the learning objective, you need to know their starting point. Then you can make informed decisions as to what supports students may or may not need to achieve the learning objective destination.

Finally, you need to have signs and checkpoints to make sure you are heading in the right direction. To get from the Chicago area to Hilton Head Island, you head southeast. You can read road signs, check a compass, look at the rise and set of the sun and stars, and more to make sure you are heading in the right direction. Likewise, you need small formative assessments that are embedded into instruction. These formative assessments can be analyzed to make sure your students are on their way to achieving the learning objective or whether they have veered from the path and need support to move in the right direction.

When teaching assessment to my preservice teachers, we go through these four steps as a linear design process.

- Articulate the destination or learning objective.

- Plan a summative assessment that will tell you whether or not the students have achieved the learning objective.

- Figure out where your students are starting from so you know what supports they may need.

- Plan several formative assessment checks along the way to make sure your students are making progress.

As mentioned, I love assessment and will come back to this topic every now and again. As the landscape of assessment is changing, so we all must become adept at designing and utilizing assessments that fit our classrooms and our instruction.

When planning for an instructional unit, ask yourself these key questions:

- What do I want my students to know, understand, and be able to do? (learning objectives)

- How will I know those objectives have been achieved? (summative assessment)

- Where are my students starting from? (pre-assessment)

- What evidence will demonstrate whether my students are making progress? (formative assessment)